Introduction

The Mediterranean diet, which is recognized for its health benefits and palatability, has been extensively studied in recent decades. In 2010, it was declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO, sparking discussions on preserving its unique cultural lifestyle. Globally, research has expanded to explore its health and environmental impacts. However, significant changes in understanding and defining the Mediterranean diet have emerged, noting a shift away from traditional dietary patterns in the Mediterranean regions and increased adoption elsewhere. Studies in non-Mediterranean countries often rigidly apply methods to assess adherence, potentially distorting their true cultural and geographical significance. Diet is more than a survival mechanism: it is a social and cultural phenomenon. The UNESCO Chair of “Health Education and Sustainable Development” promotes a “Planeterranean” approach, emphasizing diet, culture, and health globally. This review aims to provide a historical overview of the Mediterranean diet and assess its modern relevance, considering often-overlooked factors integral to its tradition and health benefits.

History of the Mediterranean diet: the original features

The original features of the Mediterranean diet are rooted in the diverse dietary habits of people in the Mediterranean area, encompassing Southern Europe, Northern Africa, and parts of the Middle East. This diet’s uniqueness stems from the region’s geographical location and favorable climate, which have historically influenced food cultivation and consumption patterns.

The agricultural revolution over 10,000 years in BC marked a significant shift in human behavior and cultural evolution. This led to settled agriculture in the Fertile Crescent, covering modern-day regions of the Middle East, parts of Turkey, and Iran. Migrating populations introduced a variety of fruits and vegetables to the Mediterranean, including early domestication of pomegranates, figs, dates, and later fruits, such as pears, apples, and citrus. The Arab and Islamic influence further enriched the region’s agriculture with vegetables, such as aubergines, spinach, and melons. Over time, other plants, such as cherry tomatoes and artichokes, have been introduced and have become integral to Mediterranean cuisine.

Three main food groups distinguished the Mediterranean diet from the others: olives, grapes, and cereals. Olives, domesticated in Persia and Mesopotamia, gained a distinctive identity in the Mediterranean through Greek and Roman civilizations, symbolizing wealth and power. Grapes, used for winemaking since ancient times, have played a significant role in the region’s economy and cultural practices, including religious rituals. Cereals, alongside pulses like peas, lentils, and chickpeas, became staples, consumed in various forms from porridge to bread, and later evolved into more complex products, such as pasta and couscous.

Overall, the history of the Mediterranean diet is a testament to the region’s rich agricultural heritage and the evolution of its culinary practices over millennia.

The Mediterranean diet in science: the main features in modern times

Modern scientific exploration of the Mediterranean diet reveals a rich history of research, beginning with a post-World War II survey in Crete by Allbaugh and colleagues. This study noted significant differences in dietary habits between Crete and the United States, particularly in the consumption of plant and animal foods. Contrary to later findings, this study initially recommended increasing the intake of animal products, viewing the traditional Cretan diet as limited owing to its lack of modernization.

Ancel Keys’ “Seven Countries Study,” conducted later in Southern Italy, is more widely recognized in popularizing the Mediterranean diet. Keys hypothesized a link between this diet and lower rates of cardiovascular disease, although some of his ideas, such as the lipid hypothesis, were later deemed overstated. This study highlights traditional Mediterranean dietary features, such as a focus on plant-based foods, legumes, cereals, pasta, bread, and limited meat, fish, and dairy intake.

Over the decades, numerous research groups have studied the Mediterranean diet. Notable among these is the PREDIMED trial in Spain, which experimentally confirmed that higher adherence to this diet reduced cardiovascular risk. Other studies have linked the Mediterranean diet to its benefits against cardiometabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and certain cancers.

Various indices have been developed to quantify the adherence to the Mediterranean diet. These indices typically consider daily or weekly food intake to determine adherence levels. They are convenient for epidemiological studies because of their wide applicability and relatively small number of food groups involved. The key components of these scores have been consistently evaluated, focusing on those aspects that most represent the Mediterranean dietary pattern and its health benefits.

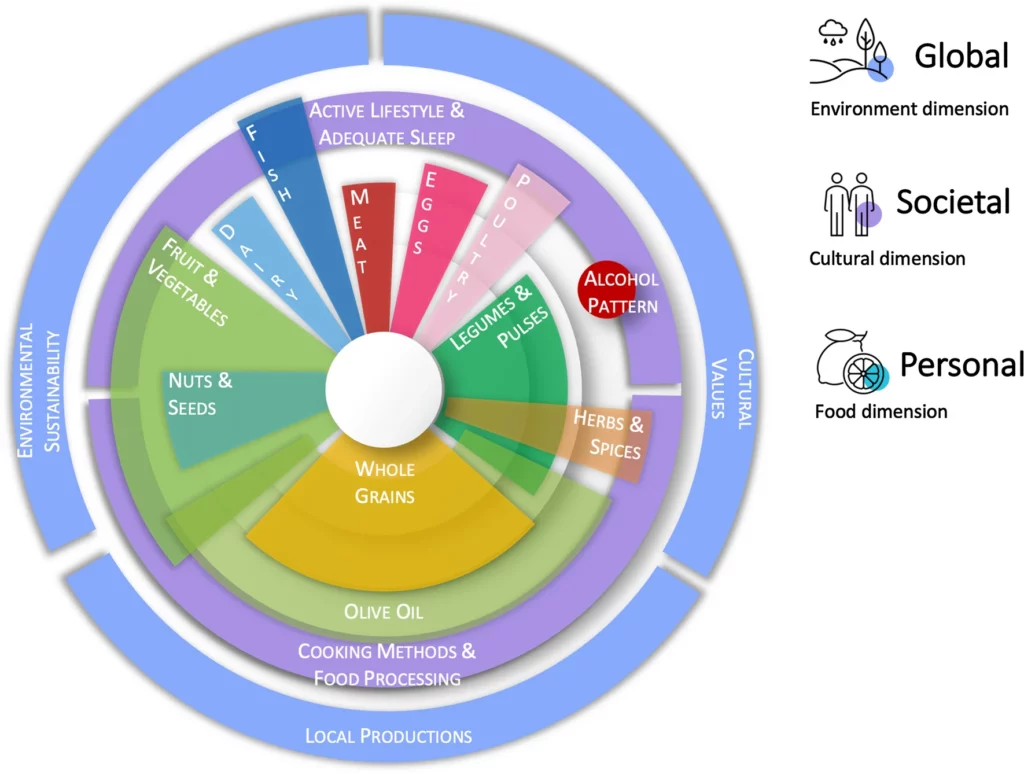

Figure 1

The modern understanding of the Mediterranean diet highlights its emphasis on plant-based foods, particularly fruits and vegetables, which are key components in all dietary indices assessing adherence to this diet. This variety has expanded over the centuries, now including a wide range of products such as green leafy vegetables, tomatoes, and artichokes, alongside fruits such as citrus berries, and regional specialties such as prickly pears and pomegranates. Fruits and vegetables are not only major sources of simple sugars, fiber, minerals, and vitamins, but also of phytochemicals, such as polyphenols, which have been linked to the prevention of chronic diseases, including certain cancers and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

Olive oil, a staple of the Mediterranean diet, is a primary source of mono-unsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and contains beneficial polyphenols, such as hydroxytyrosol. Its consumption is associated with reduced risks of cardiovascular disease and type-2 diabetes, and has been shown to improve markers of oxidative stress. Studies outside the Mediterranean region sometimes substitute olive oil intake with a ratio of MUFA to total fats, but this can introduce validity biases, as MUFAs are also found in meat.

Moderate wine consumption, particularly red wine, is another characteristic of the diet and is linked to lower cardiovascular risk owing to its polyphenol content, such as resveratrol. Whole grains, a major source of daily energy, have long been a part of the Mediterranean diet. Ancient grains, such as wheat, barley, and spelt, are staples, and in modern times, grains are consumed in various forms across the region. However, the shift from whole to refined grains in recent decades has been notable.

Legumes, another integral component, contain carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and minerals. Their consumption is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular diseases and improved blood glucose levels. Traditionally, the diet also includes limited meat intake, with a preference for unprocessed varieties. While meat is a source of high-quality protein and vitamins, excessive consumption, particularly of processed meat, has been associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease and certain cancers.

Fish consumption, historically influenced by geographical proximity to the sea, provides essential omega-3 fatty acids and is associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases and depression. However, concerns about heavy metal pollution in the Mediterranean Sea and the high sodium content in preserved fish have emerged as health considerations.

Overall, these elements define the modern Mediterranean diet, illustrating its evolution and continued relevance to health and nutrition.

Underrated aspects of the Mediterranean diet

The Mediterranean diet, renowned for its health benefits, is traditionally assessed through dietary scores and indices that often fail to capture its full essence. These methodologies typically focus on specific food items, neglecting crucial aspects, such as total daily calorie intake and the precise balance of macronutrients. A common limitation of these approaches is the equal weighting assigned to all dietary components, irrespective of their actual significance or proportion in the overall diet. Moreover, reliance on quantiles or arbitrary cutoff points for evaluating adherence can lead to inconsistencies, especially when comparing Mediterranean and non-Mediterranean populations. As a result, these tools do not fully reflect the rich cultural, culinary, and behavioral dimensions of the diet.

Significant elements of the diet, such as the consumption of eggs and dairy products, have historically been underrepresented or even excluded in many assessments owing to past concerns over cholesterol and saturated fats. However, evolving scientific perspectives now recognize the nutritional value of these foods, which are substantial sources of proteins, minerals, vitamins, and beneficial fatty acids. The incorporation of nuts and seeds, as well as a variety of herbs and spices, into the Mediterranean diet is acknowledged for its health-promoting properties. However, these components are often overlooked in conventional dietary scores. Beyond their nutritional value, they are deeply integrated into the cultural heritage and historical culinary practices of the Mediterranean region.

Another overlooked aspect is the traditional methods of cooking and food preparation, which are characteristics of the Mediterranean diet. These practices, ranging from the use of specific cooking techniques to the selection of ingredients, play a vital role in the health benefits associated with diet. Fermented foods, which are abundant in Mediterranean cuisine and offer a range of health benefits, including probiotic qualities, are also frequently ignored in mainstream dietary assessments.

To fully appreciate and understand the Mediterranean diet, it is essential to consider it more than a collection of food items. This represents a holistic approach to eating and living that combines nutritional components with rich historical, cultural, and culinary traditions. Understanding its full spectrum and health implications requires an inclusive view that transcends conventional nutritional evaluations and acknowledges the broader lifestyle and cultural context of the diet.

Pattern of alcohol consumption

The role of alcohol, particularly wine, in the Mediterranean diet is complex and nuanced. Historically, both red and white wines have been consumed in the Mediterranean region, and more recently, beer production and consumption have also grown in southern European countries. Moderate wine consumption has been identified as a key aspect of the traditional Mediterranean diet, contributing significantly to its overall health benefits observed in large population studies within the Mediterranean basin.

However, alcohol is recognized as a carcinogen and is associated with various health risks, leading to recommendations for its exclusion from diets. While the alcohol content in wine and beer is relatively low and their polyphenol content may contribute to cardiovascular benefits, it’s the pattern of alcohol consumption within the Mediterranean diet that sets it apart. Typically, alcoholic beverages are consumed in moderation during meals. This contrasts with the patterns studied in most alcohol-related health studies, which often do not distinguish between the context of consumption (during meals versus outside meals) and the pattern (regular moderate consumption versus binge drinking).

Observational studies and large meta-analyses have suggested that moderate alcohol intake may reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and overall mortality. However, even low consumption levels have been linked to increased risks of certain cancers, such as breast, liver, and colon cancer. Interestingly, a J-shaped relationship was observed between alcohol consumption and the risk of various diseases, indicating potential benefits at moderate levels but increased risks at higher levels of consumption.

Most existing research on the health effects of alcohol has been conducted in populations outside the Mediterranean region, where drinking patterns differ significantly from those of the traditional Mediterranean diet. Therefore, future studies are needed to investigate the impact of different drinking occasions and patterns more precisely. These studies could provide a clearer scientific basis for recommendations on alcohol consumption, balancing the need for caution against potential benefits when consumed moderately or as part of meals.

Local production and environment preservation

The concept of local production and environmental preservation is a key aspect of the Mediterranean diet and is becoming increasingly relevant in discussions about sustainable food systems. The Mediterranean diet, with its emphasis on seasonal, locally sourced foods, minimally processed, and produced with eco-friendly agricultural practices, offers a model closely aligned with the “planetary diet” advocated by the EAT-Lancet Commission. This approach to diet is not only about health benefits, but also about sustaining the environment and local economies.

Traditionally, the Mediterranean diet has been characterized by foods that are locally produced and minimally processed, taking advantage of the region’s unique climate and biodiversity. This includes practices, such as crop rotation and mixed cultures, which are sensitive to local environmental conditions and maintain soil health. However, globalization and mass production have shifted this paradigm, introducing year-round availability of products from global sources, which brings about significant environmental impacts often overlooked in the scientific literature.

Intensive farming practices, even for typical Mediterranean products such as olives and olive oil, can have detrimental environmental effects. Sustainable farming practices, reminiscent of traditional methods, are suggested as a means of mitigating these impacts. Such practices include agroecological methods that are free from chemical pesticides, which promote natural biodiversity and reduce chemical exposure.

Traditional agricultural systems, such as olive-based agroforestry, play a crucial role in preserving habitat diversity, landscape complexity, and soil health. Consuming seasonal and local produce reduces the ecological impact of transportation and often requires fewer pesticides and alternative growing methods, thus enhancing the nutritional quality of food.

This approach also supports dietary diversity, as the natural biodiversity of the Mediterranean Basin influences agricultural practices and food availability throughout the year. Furthermore, they foster economic sustainability by supporting local economies and small-scale producers.

Level of food processing

The increasing focus on food processing in the context of the Mediterranean diet has revealed growing concerns regarding the health impacts of ultra-processed foods (UPFs). Recent classifications categorize UPFs as products that undergo extensive industrial processing involving significant alteration of the original food matrix and the addition of non-natural ingredients. These changes are aimed at enhancing durability, aesthetics, texture, and palatability. However, high consumption of UPFs is emerging as a potential health risk.

Studies have shown that diets high in UPFs are often nutritionally poor, characterized by high levels of added sugars, sodium, and trans-fatty acids, and a lack of fiber, protein, and essential micronutrients. Moreover, concerns have been raised about industrial, mass-produced, ready-to-eat products that can replace fresh or traditionally cooked foods. Despite potentially aligning with dietary recommendations in terms of nutrients, the presence of natural or artificial additives and preservatives in these foods is considered a health hazard.

Evidence suggests a strong association between UPF consumption and various health issues, including obesity, cardiometabolic disorders, overall mortality, and mental health problems. However, there is some criticism regarding the definition of UPFs, particularly regarding the parameters used for identification and the wide range of foods included in this category, which can lead to unreliable comparisons across different populations.

In countries such as the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, UPF consumption constitutes up to 80% of the daily energy intake. By contrast, Mediterranean countries have a significantly lower average consumption rate of approximately 20%. Studies have found that higher adherence to the traditional Mediterranean diet is correlated with lower UPF consumption. The Mediterranean dietary pattern is inherently linked to the region’s cultural background and daily lifestyle, emphasizing fresh, natural foods over pre-packaged alternatives and the preservation of culinary traditions.

However, owing to globalization and shifting lifestyles, UPFs are increasingly becoming a part of the diet in Mediterranean countries. This changing reality suggests that future research on the Mediterranean diet should incorporate an analysis of the level of food processing. This would provide a more accurate assessment of adherence to diet, distinguishing between unprocessed, minimally/culinary processed, and heavily processed foods.

Physical activity

The concept of the Mediterranean diet extends far beyond food choices and encompasses a comprehensive lifestyle approach. Originating from the Greek word “dìaita,” meaning “lifestyle,” the Mediterranean diet historically integrates dietary habits with daily behaviors, including significant physical activity. This aspect is often overlooked in modern interpretations and discussions of diet.

Historically, the Mediterranean diet was part of a lifestyle that included high levels of physical activity, especially among southern Italian farming communities studied in the 1960s. These farmers, who consumed a diet rich in carbohydrates from whole grains and legumes, balanced their intake with their physically demanding daily activities. This harmony between diet and physical activity is crucial for maintaining health and wellbeing.

However, over the decades, there has been a significant shift in these traditional lifestyles. Physical activity, once an integral part of daily labor and commuting, has been largely replaced by motorized transport and limited to recreational purposes, often only pursued by those who are particularly health conscious. This reduction in physical activity has significant global health implications, contributing to an increase in mortality associated with sedentary lifestyles.

The benefits of physical activity are well documented, ranging from improved cardiometabolic health to enhanced mental well-being, leading to longer life spans and reduced disability. Studies have consistently shown that combining dietary interventions such as adherence to the Mediterranean diet with increased physical activity has a greater impact on health and body weight management than either approach alone. Moreover, there is evidence of a synergistic effect on mortality risk when high adherence to the Mediterranean diet is combined with high physical activity levels. This finding highlights the need for further research on the interaction between these two variables, emphasizing the importance of viewing the Mediterranean diet as part of a broader, more holistic lifestyle approach.

Circadian rhythm and sleeping patterns

The relationship between diet and brain health is an increasingly important focus in nutritional science, reflecting a broader interest in how lifestyle factors, including diet and sleep, interconnect to health. Current research is exploring the mechanisms by which food influences the brain, such as through the gut microbiota, but the specific clinical manifestations of this relationship remain under investigation.

Historically, the traditional Mediterranean lifestyle, exemplified by southern Italian farmers studied by Ancel Keys and older Mediterranean islanders, integrated early rising, active days, frugal meals, mid-day rests or naps, and early dinners. This routine aligns with the concept of a “morning chronotype,” where individuals are naturally inclined to be active earlier in the day. Recent studies have suggested that this chronotype is associated with higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

Sleep hygiene, along with eating patterns such fasting and time-restricted eating, is gaining attention for its potential health benefits. These practices involve alternating periods of fasting or limiting the daily eating window, which is thought to be in harmony with natural circadian rhythms in the human body. Traditional Mediterranean lifestyles, with regular sleeping patterns aligned with sunlight exposure and fewer eating occasions, starkly contrast modern lifestyles that often involve irregular eating and sleeping patterns.

The human body appears to be better adapted to food intake restricted by daylight hours, reflecting our ancestral biology. Eating patterns that align with these natural rhythms can affect metabolic and neuronal network activities, and regulate various body functions. Such dietary patterns have been linked to a reduced risk of non-communicable diseases including cardiovascular diseases, metabolic risk factors, certain cancers, and cognitive and affective disorders.

Although research in this area is growing, it often treats dietary and lifestyle factors as separate entities. Some studies have explored the benefits of time-restricted eating, such as during Ramadan or skipping breakfast or dinner, within the context of the Mediterranean diet, showing positive effects on metabolic health. Conversely, social jetlag, or a mismatch between an individual’s circadian rhythm and the external day, is associated with poorer diet quality and a departure from traditional dietary patterns.

Overall, the integration of diet with other lifestyle factors such as sleep and physical activity forms a holistic approach to health, reflecting the interconnected nature of these elements in maintaining well-being.

Social and cultural values

The culture of increased takeaway and ready-to-eat food consumption in Westernized societies, and its consequences, highlights a significant departure from the holistic approach of the Mediterranean diet. This shift not only affects physical health through the disruption of circadian rhythms, sleep disorders, and potential nutritional deficiencies but also impacts mental well-being, potentially leading to social isolation and depressive symptoms. An essential aspect of this change is the diminishing involvement in the entire process of food preparation and consumption, which has historically been a fundamental part of the Mediterranean lifestyle.

In the context of the traditional Mediterranean diet, especially as observed in the 1960s, meals were not only about food intake; they represented moments of social interaction, communication, and conviviality. Social engagement in cooking and sharing meals plays a crucial role in community bonding and mental health. Currently, this aspect of shared meal preparation and enjoyment is often overlooked in studies exploring the relationship between the Mediterranean diet and health outcomes. This omission undermines the potential impact of social engagement on mental health and general wellbeing.

Frugality, another key principle in the classical Mediterranean diet, is intertwined with social values. Meals were occasions for social gatherings aimed at establishing and maintaining social structures such as family bonds or hospitality among friends and guests. These meals are often marked by frugality and moderation, in contrast to the continuous snacking and solitary eating habits prevalent in modern lifestyles. The traditional Mediterranean diet’s emphasis on shared meals and communication during dining contrasts starkly with the contemporary habits of eating alone, often in front of screens, and with little to no social interaction.

The failure to assess the social and cultural elements of the Mediterranean diet in contemporary dietary studies points to a significant gap in our understanding. The totality of dietary indices typically fails to consider the lifestyle and cultural beliefs associated with adherence to the diet, thus missing a critical dimension of what originally defined the Mediterranean diet. Reintegrating these aspects, including promoting cooking skills and encouraging family or group meals, could provide a powerful and empowering approach to health care and prevention, addressing both physical and mental health needs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the essence of the Mediterranean diet extends far beyond mere collection of food items; it is deeply rooted in the history, lifestyles, traditions, and cultural fabric of the populations residing in the Mediterranean region. This diet is not simply a list of ingredients or set of nutritional guidelines to be followed in isolation. Instead, it represents a holistic lifestyle that intricately weaves dietary patterns, cultural heritage, social interactions, and traditional practices together.

The study of the Mediterranean diet must transcend the boundaries of conventional dietary analyses. It should encompass the broader context of how this diet interacts with the lifestyle and cultural heritage of Mediterranean people. While the need for a simplified approach to study the health benefits of diet, especially for applicability to non-Mediterranean populations, is understandable, such reductionism can overlook crucial elements. These elements include the social and environmental aspects of food production and consumption, the role of physical activity, and the importance of mealtime as a communal social event.

Recognizing the multifaceted nature of the Mediterranean diet, future research should explore and integrate these often underrated aspects. These include patterns of food consumption and preparation, the social and cultural significance of meals, and the environmental impact of dietary choices. In doing so, we can lay the foundation for a more comprehensive understanding of the Mediterranean diet. This approach can inform the development of a “Planeterranean” diet, a concept that applies the principles of the Mediterranean lifestyle to the global context, promoting health, sustainability, and social well-being on a broader scale.

Read all at: Godos, J., Scazzina, F., Paternò Castello, C. et al. Underrated aspects of a true Mediterranean diet: understanding traditional features for worldwide application of a “Planeterranean” diet. J Transl Med 22, 294 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05095-w