Although the MD has often been associated with the “eternal trinity” of wheat, olive oil, and wine, it also embodies the essence of traditional agricultural practices and dietary habits, which are marked by a culture of sharing and reciprocity [

4]. For instance, wealthy urban Greeks favored a diet rich in vegetables, grains, legumes, olive oil, and wine. Barley and wheat were used for oatmeal and bread, whereas various legumes such as fava beans, chickpeas, lentils, lupines, and peas were either prepared in specific dishes or incorporated into flour for bread and oatmeal [

5]. A typical MD is characterized by several key features: substantial consumption of vegetables, fruits, legumes, and grains (including complex carbohydrates and dietary fiber), limited total fat intake (<30%), low saturated fat intake (<10%), emphasis on monounsaturated fats, and moderate alcohol consumption (primarily wine) [

6]. Over time, the introduction of new ingredients and influences from regions such as Asia and the Americas, including tomatoes, potatoes, maize, beans, and cane sugar, have resulted in changes in Mediterranean cuisine, expanding its culinary horizons beyond indigenous roots. Throughout different historical eras, cultures, religions, agricultural practices, and economic circumstances, the emphasis on food elements within the MD has varied. Additionally, factors such as climate, economic challenges, and scarcity have played a significant role in shaping this diet rather than relying on intellectual foresight or deliberate dietary planning, which is often the approach adopted in modern times to create popular diets. This might explain why it has been challenging to precisely characterize this dietary regimen, as it exhibits unexpected complexity and variations across different countries and historical periods. In 2010, the MD gained recognition as an Intangible Cultural Heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The official submission made to UNESCO characterizes the MD as “a social tradition rooted in a collection of competencies, wisdom, customs, and traditions that encompass everything from the natural environment to culinary practices. These encompass activities such as cultivation, harvesting, fishing, preservation, processing, cooking, and, most notably, consumption, particularly within the Mediterranean region” [

7]. In 2011, the Mediterranean Diet Foundation in Spain, in collaboration with experts in the field, revised the “classic” MD pyramid to accommodate changes brought about by modernization and to integrate cultural and lifestyle aspects [

8]. A literature review by Davis et al. (2015) attempted to establish an integrated definition of the MD. In conducting their analysis, the authors considered a variety of criteria, including general descriptive terms, recommended serving sizes of key food groups, and nutrient content [

9]. Based on this comprehensive review, the authors defined daily dietary intake as follows: vegetables, 3–9 servings; fruits, 0.5–2 servings; cereals, 1–13 servings; and olive oil, up to 8 servings. In terms of energy content and macronutrient composition, the MD typically consists of approximately 2220 kcal/day, with fat accounting for 37% of the total calories [

9]. Regardless of the definition adopted, there is a consensus regarding the health benefits of the MD. Since Ancel Keys’ pioneering research revealed that the dietary practices of Mediterranean countries are associated with longer lifespans and reduced incidences of coronary heart disease (CHD), many more studies have been published [

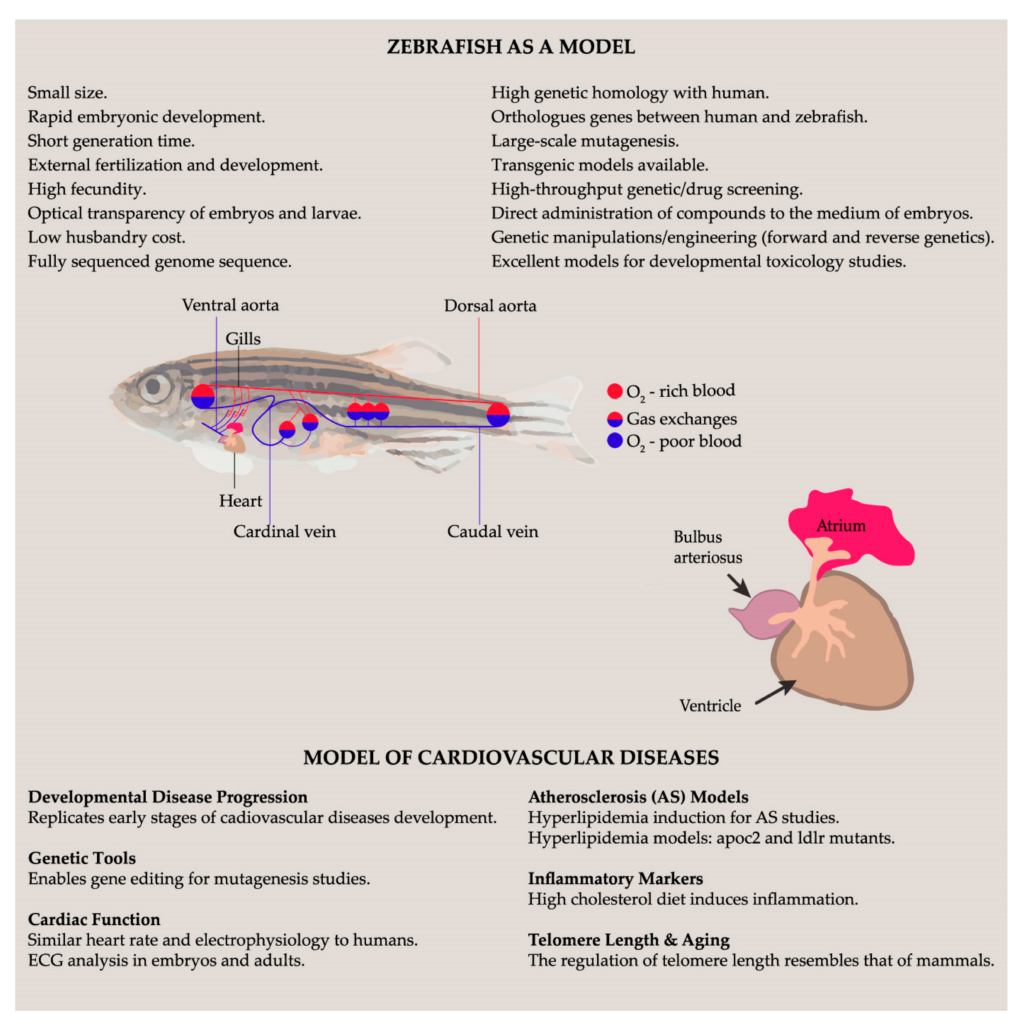

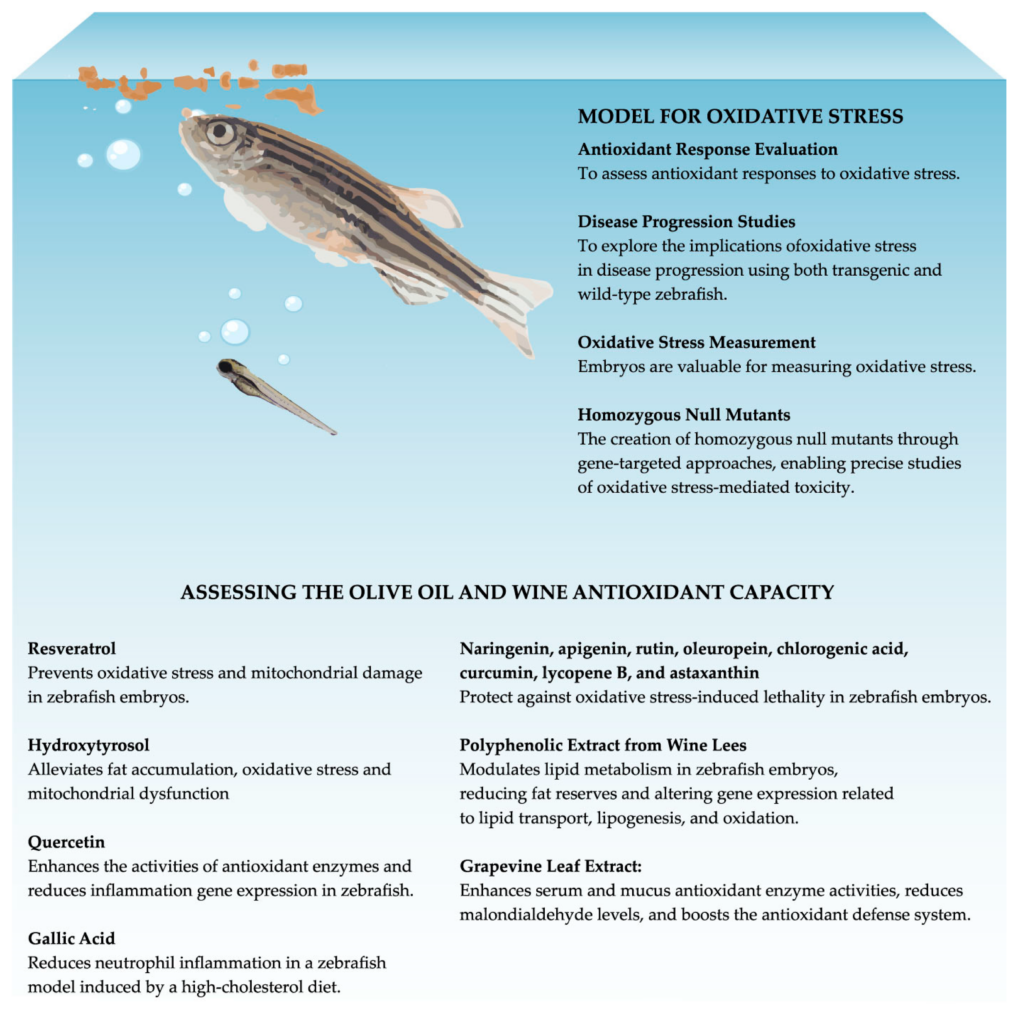

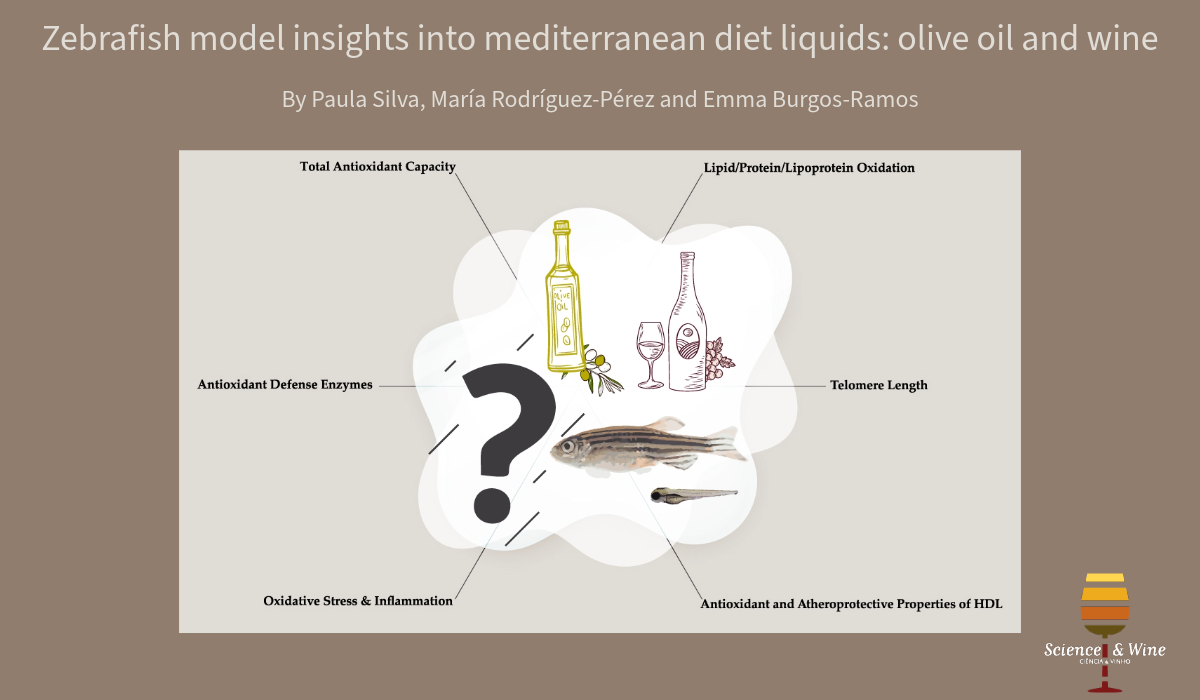

1]. In the following section, we present a summary of the effects of the MD on longevity and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) derived from observational studies. In our opinion, reliable information regarding dietary effects in humans, especially in those suffering from a specific illness or disorder, requires clinical investigation based on well-constructed preclinical data relevant to the intended human population. Moreover, modern research requires animal studies, such as the analysis of signaling pathways under various conditions or examination of novel dietary approaches. Basic research can benefit from combining animal and human data. Therefore, it is necessary to work with animal models that share genetic similarities. This helps confirm the changes observed in animals after specific treatments in humans. Thus, translational research using observational studies allows for the identification of associations between basic research and humans, even before new experimental strategies are approved and tested in randomized controlled trials (RCTs).