By Carla Marano-Marcolini, Ana Isabel Costa and Manuel Malfeito Ferreira

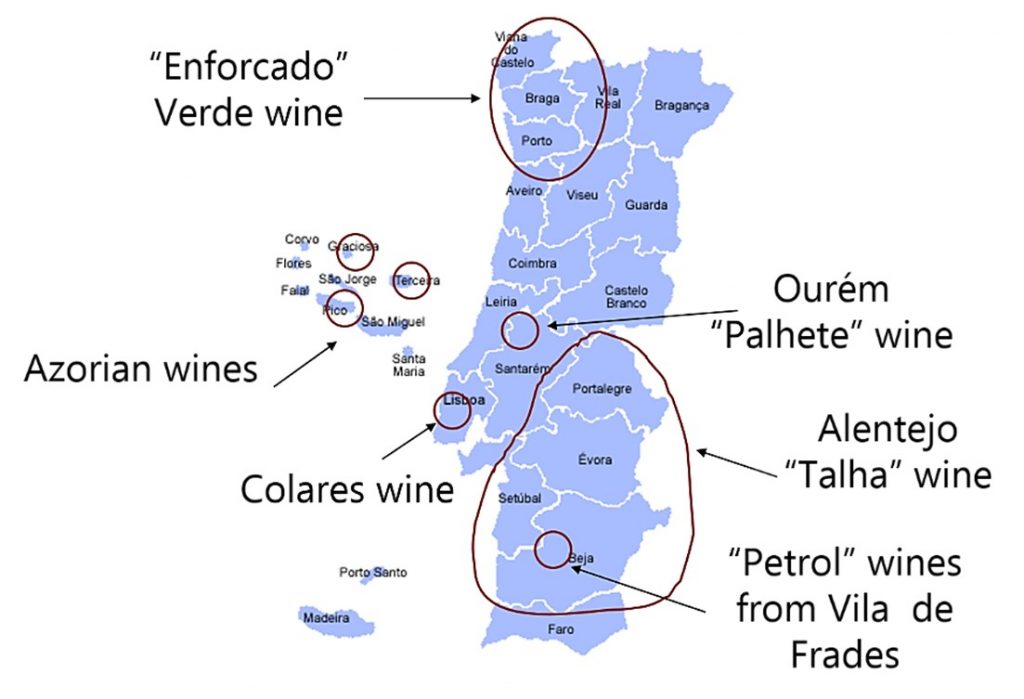

Portugal has an important winemaking sector, currently holding the seventh largest vineyard area in the world and ranking first globally in terms of dedicated share of total planted agricultural area (14% over 200.000 ha). The sector therefore has a major economic impact on the country. Nevertheless, traditional, small local producers still struggle to be recognized and appreciated amongst the rising number of Portuguese wine brands. In 2008, the Association of the Historical Wines of Portugal (AVHP) was born with the aim of protecting and preserving Portuguese wine culture and heritage. This was the first body to propose the creation of Vinhos Históricos de Portugal, or the Historical Wines of Portugal (HWP), classification. According to AVHP, a combination of geographical origin, use of traditional grape varieties and application of ancestral viticulture/oenology practices characterize HWP and their production. Examples of these wines (Figure) are Vinho Verde Enforcado (Minho), Palhete Medieval de Ourém (Encostas D’Aire-Lisboa), Vinho do Chão de Areia de Colares (Sintra-Lisboa), Vinho da Talha/Vinho Petroleiro (Alentejo) and Vinho do Pico (Pico-Azores).

Due to their history, pedigree, small scale and traditional forms of production, wines classified as HWP might have a natural advantage in being perceived as singular and authentic products. However, at the same time, they remain largely unfamiliar to most consumers, even those typically knowledgeable about Portuguese wines, and are often singular or downright peculiar products in terms of their sensory profile, packaging and distribution channels [1]. Their increased market acceptance is therefore likely contingent on the adequate provision of contextual knowledge, enabling their proper degustation and the appreciation of their unique features, including their regional character and heritage status.

Moreover, studies on the product, individual and situational factors affecting how consumers understand and judge the authenticity of food and wine brands remains scarce [2,3]. This study aimed to (1) identify the authenticity attributes consumers associate with wines classified as HWP; (2) assess the relative strength of these associations; and (3) examine how this varied across groups of consumers with different levels of wine knowledge. To this end, we conducted interviews with Portuguese wine producers (n=3) and consumers (n=12), as well as an online questionnaire with a large, convenience sample of the latter (n=641).

A three-cluster solution was obtained from brand authenticity dimension regression scores, with the smallest cluster comprising 153 respondents, the middle-sized one 224 and the largest one 264. The dimensions of authenticity associated with HWP by respondents in the smallest cluster were first “uniqueness and relationship to place”, followed closely by “quality and authentication”. “Time and tradition” and “production and marketing” were both less closely associated with this wine concept. In view of this, they were collectively labelled Heritage Gatekeepers. The dimensions of authenticity associated mostly with HWP by respondents in the middle-sized cluster were “quality and authentication”, followed closely by “uniqueness and relationship to place”. However, they also closely associated “time and tradition” with this concept, contrary to Heritage Gatekeepers. The difference of their average associations with “production and marketing” was also much higher. In view of this, respondents in this cluster were collectively named Traditional Revivalists. The dimension of authenticity associated mostly to HWP by respondents in the largest cluster was “uniqueness and relationship to place”. Respondents in this cluster associated “production and marketing” with this wine concept the least. Associations with the remaining two dimensions of authenticity were similarly moderate. Consequently, this cluster of respondents was named Aspirational Explorers.

Results indicated that, compared to Aspirational Explorers, wine connoisseurs emerged as a group of Heritage Gatekeepers in terms of their perceptions of the HWP brand. Indeed, they associated origin, cultural heritage, quality, reputation and at-home consumption more strongly with wines labelled as HWP, and tradition, wine age, production characteristics and out-of-home consumption less strongly. Such results suggest that high product knowledge is likely essential for consumers to recognize a wine classified as HWP as a novel, distinct and strictly defined table wine concept, not to be confused with other categories of wine already marketed for centuries (e.g., vintage Port) but, by and large, not sharing similar production characteristics, and hence not warranting this classification.

Similar to what was found by previous research [4], Heritage Gatekeepers reportedly bought wine more often and appeared to be willing to pay higher prices for it than respondents in the remaining clusters, which exhibited lower wine knowledge. They also seemed to attach more value to the origin of wine, the terroir and other production characteristics, such as harvest year, than novices [5–6]. Altogether, the findings presented in this work reinforce the importance of segmenting potential HWP consumers according to their general level of wine knowledge, and of developing strategies for the positioning of these wines that take the existence of different knowledge-based segments well into account. Ensuing marketing communication activities should thus focus, first and foremost, on teaching wine novices such as Traditional Revivalists what the HWP classification stands for, as well as in terms of institutional authenticity [7], and where wines classified as HWP can be purchased. Those targeting savvier wine consumers should focus instead on reinforcing their terroir-based authenticity perceptions of the wines falling under this classification.

Read more at: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/10/5/979

Carla Marano-Marcolini

Ana Isabel Costa

Manuel Malfeito Ferreira

Carla Marano-Marcolini has a PhD in Marketing and Consumption and is an Adjunct Professor at the University of Jaén (Spain). She participated in national and international conferences and published books and papers on agri-business and consumer behaviour on international journals. She received the Best Communication Award by the Spanish Association of Academic and Professional Marketing (AEMARK-2016) and the VII Research Award of the Economic and Social Council of the province of Jaén. Her main areas of research are agri-food marketing, agricultural policy and rural tourism.

Ana Isabel Costa is FCT Principal Research Associate in Marketing and Consumer Behavior at the CATÓLICA-LISBON School of Business and Economics of Universidade Católica Portuguesa. She holds a PhD in Consumer Behaviour and New Product Development from Wageningen University, a Master in Food Quality Management from Ghent University and a Licenciatura em Engenharia Agro-Industrial from Instituto Superior de Agronomia in Lisbon. Her research focuses on the self-regulation of food consumption, its associations with diet, health and sustainability, and the development of novel foods. She leads several nationally and internationally funded research projects at the Food Behavior Lab (https://www.foodbehaviourlab.com).

Manuel Malfeito Ferreira is an Assistant Professor at the Instituto Superior de Agronomia (ISA), University of Lisbon, teaching classes related with Food and Wine Microbiology since 1987. His research is mainly related with food and wine spoilage yeasts especially concerning volatile phenol production by Brettanomyces bruxellensis. Another topic is the study of microbial ecology of the vineyard environment, aiming at understanding the dissemination of spoilage species by analysing the microbiota of damaged grapes. Recently, he begun a research line to understand wine appreciation under the consumer perspective. His work is published regularly in peer-reviewed journals and is co-author of several book chapters, being frequently invited to speak in technical seminars all over the world. Since his first work in the production of sparkling wine by the continuous method, in 1986, he is winemaker for several Portuguese wineries and organizes cultural events to promote wine education among consumers.

References

- Loureiro, V. Historical wines of Portugal. Chron. Hortic. 2009, 49, 13–14.

- Pelet, J.-É.; Durrieu, F.; Lick, E. Label design of wines sold online: Effects of perceived authenticity on purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102087, doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102087.

- Youn, H.; Kim, J.-H. Effects of ingredients, names and stories about food origins on perceived authenticity and purchase intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 63, 11–21, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.01.002.

- Johnson, T.E.; Bastian, S.E. A Preliminary study of the relationship between Australian wine consumers’ wine expertise and their wine purchasing and consumption behaviour. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2007, 13, 186–197, doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2007.tb00249.x.

- Chocarro, R.; Cortiñas, M.; Elorz, M. The impact of product category knowledge on consumer use of extrinsic cues—A study involving agrifood products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 176–186, doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2008.09.004.

- Famularo, B.; Bruwer, J.; Li, E. Region of origin as choice factor: Wine knowledge and wine tourism involvement influence. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2010, 22, 362–385, doi:10.1108/17511061011092410.

- Spielmann, N.; Charters, S. The dimensions of authenticity in terroir products. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2013, 25, 310–324, doi:10.1108/IJWBR-01-2013-0004.