By Kateřina Dadáková

For plants, the interaction with their environment is particularly important due to two reasons. First, plants cannot move and escape the adverse conditions and second, they need to have a large surface to catch as much light and nutrients as possible and therefore, the contact of the plant with the environment is intense. To rise to this challenge, plants synthesize an enormous number of different specialized metabolites, which help them to withstand unfavourable weather conditions, cooperate with their symbionts, or fight their pathogens and competitors. Notably, these metabolites often interact also with the human microbiota (including pathogens) or with components of human metabolism, bringing health benefits to those who consume them.

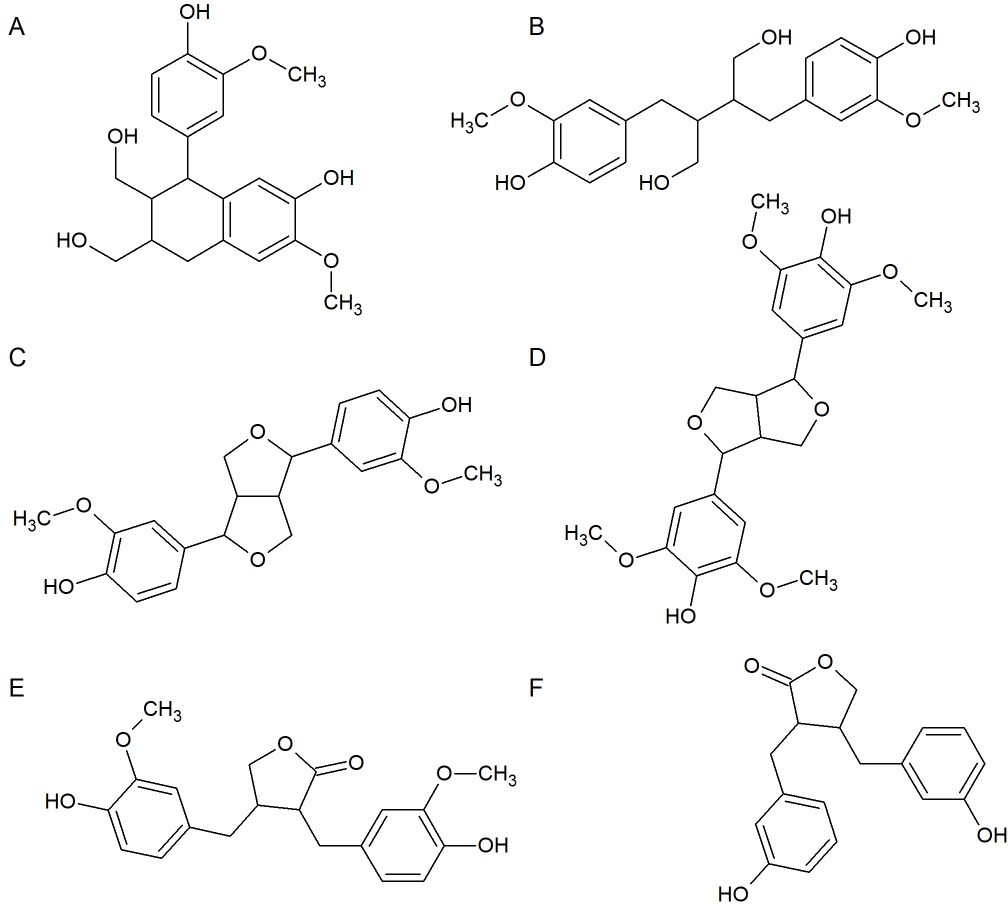

Lignans belong to these beneficial plant-derived compounds. They are predominantly found in plant grains and seeds and among other foodstuffs, they are contained in wine. In different types of wine, different lignan structures can be found, namely, lyoniresinol, isolariciresinol, and secoisolariciresinol and to a lesser extent matairesinol, lariciresinol, and syringaresinol (Fig 1). The concentrations of lignans in different wine types range from 0.1 to 3.3 mg/L, a significant part of them in the form of glucosides. Following ingestion, lignans are deglycosylated and metabolized by both human cells and intestinal microorganisms. Parent lignans as well as their metabolites, most importantly enterolactone and enterodiol, possess antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and oestrogen-like activities. As such, lignans can exert beneficial effects on chronic inflammation, menopausal symptoms, and oestrogen-related cancer types. Furthermore, some lignan species have been reported to reduce cardiovascular diseases.

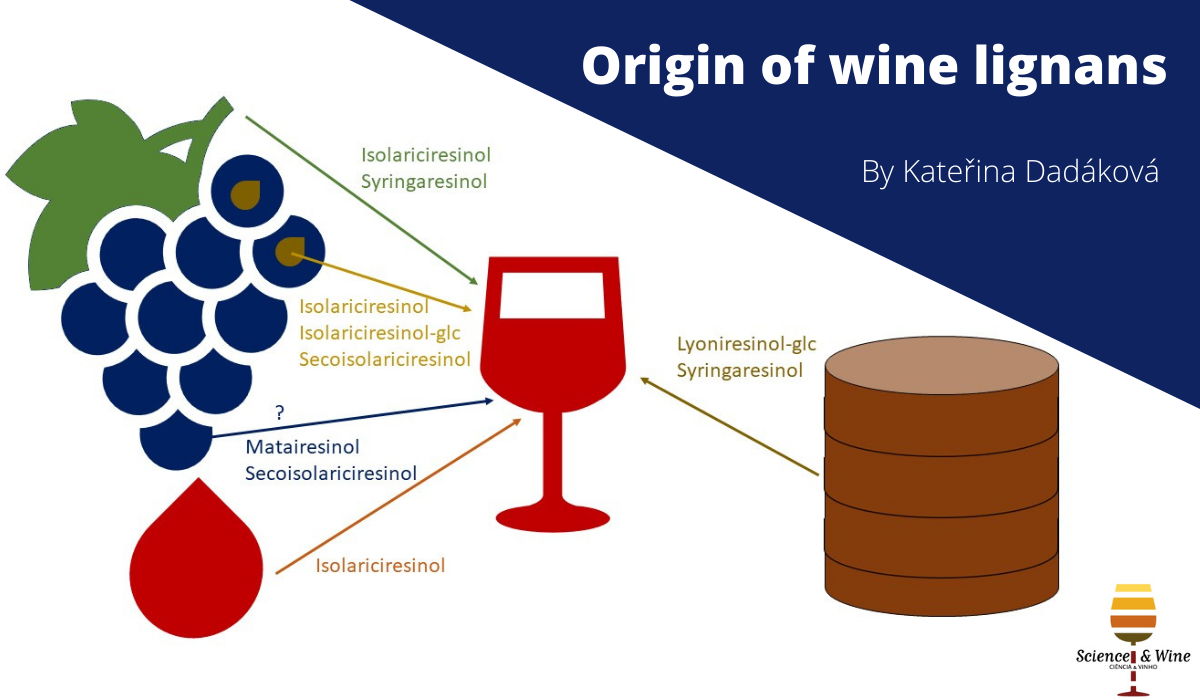

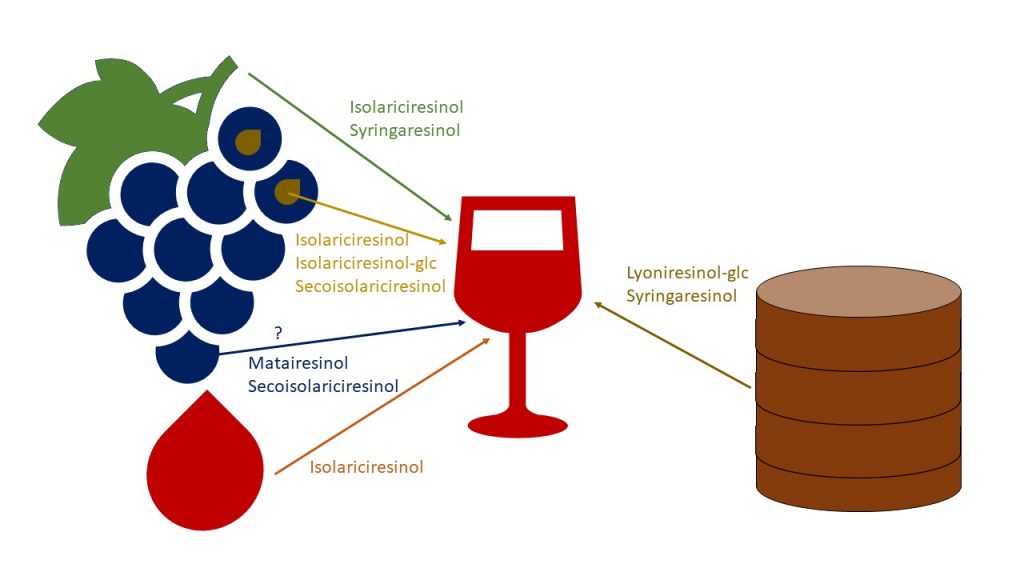

To increase the health benefits associated with a higher intake of lignans, enriching wine with different lignans is desirable. However, from the different lignan species contained in wine, the origin of only one was proven before. It is lyoniresinol and it is found in wines aged in oak barrels, as it comes from oak wood. The origin of all other wine lignans was unknown; therefore, we analysed lignans in must, seeds, stems, and wine prepared using stainless steel tanks, oak barrels, and the Qvevri method, that is on-skin fermented white wines in clay vessels, to determine, which lignans come from the different parts of the grape bunch, and which are released from the wood.

Using LC-MS analytical method, we found a low concentration of isolariciresinol in the must, a number of lignan species in the grape seeds (isolariciresinol, isolariciresinol glucoside, secoisolariciresinol, pinoresinol, and lyoniresinol glucoside), and isolariciresinol together with syringaresinol in the stems. Furthermore, lyoniresinol and syringaresinol were previously identified in oak wood. Consistently, we found out that the maturation procedure in contact with grape seeds resulted in higher concentrations of isolariciresinol, isolariciresinol glucoside, and secoisolariciresinol. Maturation in contact with grape stems resulted in higher concentrations of isolariciresinol and syringaresinol, and maturation in contact with wood resulted in higher concentrations of a compound putatively identified as lyoniresinol glucoside and of syringaresinol.

On the ground of these results, we conclude that lyoniresinol and syringaresinol originate from oak wood and from the wooden parts of both the grape bunch and the barrel, respectively. Isolariciresinol can be released into the wine from all parts of the grape bunch and secoisolariciresinol comes from the grape seeds and possibly also from the berry skins (Fig. 2). Pinoresinol, although present in relatively large quantities in the grape seeds, is not released into the wine. Furthermore, we hypothesize that low amounts of matairesinol may be released into the wine from the grape skins. We believe that these findings will enable winemakers to enrich the wines with particular lignan species by using different wine preparation technologies.

Dadakova K, Jurasova L, Kasparovsky T, Prusova B, Baron M and Sochor, J (2021) Origin of wine lignans. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. doi: 10.1007/s11130-021-00928-1

Kateřina Dadáková works as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biochemistry at Masaryk University and as a Postdoc at the Institute of Animal Physiology and Genetics at Czech Academy of Sciences. She has received the Ph.D. degree in Biochemistry at Masaryk University in Brno (Czech Republic) in 2015. Her research interests include plant specialized metabolites and their roles in crop performance and food quality. Dr. Dadáková has (co)authored 15 scientific research articles in indexed journals. She serves as a member in the editorial board of the Springer journal Plant Foods for Human Nutrition and in the reviewer board of the MDPI journal Separations.