By David de Meza and Vikram Pathania

It is a truth almost universally acknowledged that ordering the second-cheapest wine in a restaurant is a no-no. According to former Wall Street Journal wine columnists John Brecher and Dorothy Gaiter, “…the cheapest wine on the list is often a fine value, while the second-cheapest wine on the list is almost always the worst value, since people don’t want to appear penurious by ordering the least expensive wine on the list.”. An article in the Daily Telegraph from 2014, “Why you should never order the second-cheapest wine” delivers the same message, as does a column by best-selling behavioural economist Dan Ariely.

The phenomenon on which the adage is based is brought to (cartoon) life in an episode of the Simpsons from 1990 when Homer bellows “Garcon! Another bottle of your second-least-expensive champagne”

Is it true though that the second-cheapest wine really is overpriced? There is reason to doubt. Perhaps diners don’t regard ordering the cheapest wine as uniquely embarrassing. Perhaps the wide circulation of the embarrassment theory makes the second-cheapest wine even less attractive than the cheapest since it is not only believed to be a bad buy, but signals a pitiable effort to appear affluent. Even if diners do behave as naïve behavioural types, restaurateurs may choose not to exploit them, if only because doing so makes the more sophisticated types distrustful of the list.

We decided to test the claim, not by drinking our way through the wine list of top London restaurants on expenses, alas! Instead, we scraped the wine list of 249 London-based restaurants collecting information on the 6335 wines listed. As well as the menu price, the name, description, and vintage year of the wines were run through Wine-searcher.com that gives the cheapest available retail prices. The mean % mark-up over retail (100*margin/retail) was about 303% – very similar for both red and white wines.

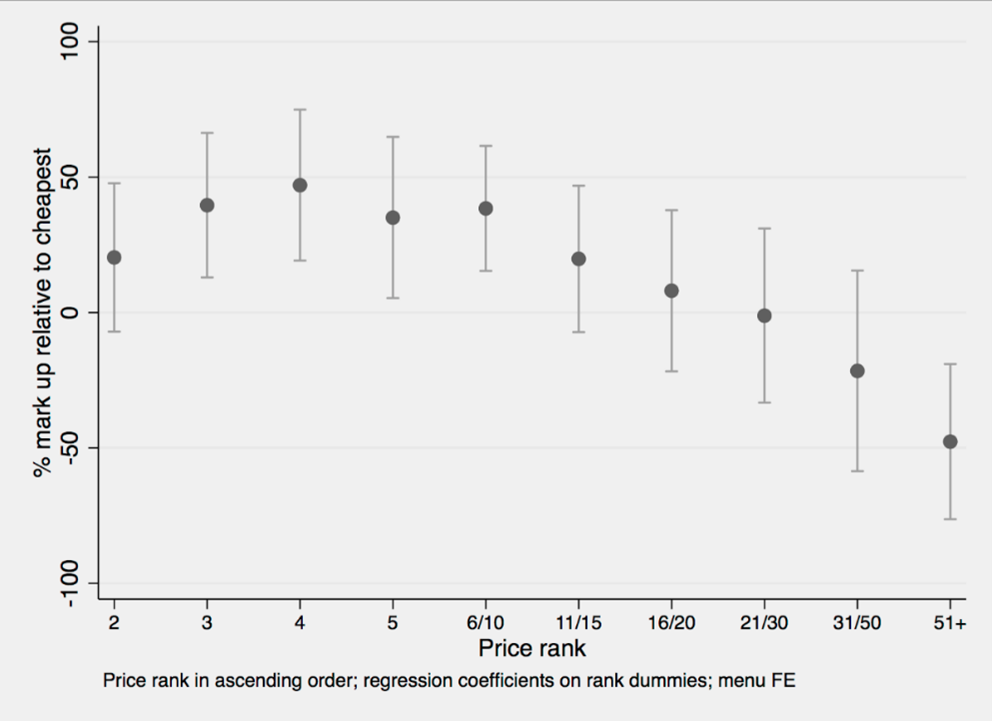

Embarrassment theory proposes that restaurateurs exploit the enhanced willingness to pay of naïve diners for whatever wine is the second cheapest. The test is therefore whether this wine commands a mark-up above that of its neighbours. What we found is in the Figure. The second cheapest wine does not stand out from the rest. In fact, the % margin over retail is significantly below that on the third, fourth and fifth cheapest wines. A second test that restricts comparisons to the exact same wine appearing at different ranks in different restaurants finds similar results.

What is apparent is that percentage mark-ups are highest on mid-range wines. A possible explanation for this inverse-U pattern is that at the low end, margins are kept down to encourage wine consumption. At the high end, setting a relatively low margin tempts diners to upgrade to wines with higher absolute mark-ups without causing any diners to downgrade to less profitable wines.

We also found that choosing to buy by the glass rather than by the bottle does not put drinkers significantly out of pocket. On average, a large glass (250 ml) costs less than 7% more per unit volume compared to the bottle.

It is a plausible story that gouging restaurateurs exploit naive diners whose main concern is not so much what they drink as not being exposed as stingy in a relatively public arena. As far as we know the claim has never been investigated empirically. Our data suggests that it is an urban myth that the second-cheapest wine is a poor choice.

David de Meza

Vikram Pathania

David de Meza is the Eric Sosnow professor of management at LSE and a former editor of the Economic Journal and Economica. Vikram Pathania is an associate professor of economics at the University of Sussex.

References:

de Meza, David and Vikram Pathania (2021) “ Is the Second Cheapest Wine a Ripoff?” Economic Letters 205.

de Meza, David and Vikram Pathania (2021) “ Is the Second Cheapest Wine a Ripoff? Economics vs. Psychology in Product Line Pricing” American Association of Wine Economists, Discussion Paper 264