By Camilla Farolfi

Sustainability is more and more a focal topic in business orientation, in governments’ strategies, and in guiding consumer choices worldwide. Nevertheless, the concept of “sustainability“ is quite complex and broad, relying on the definition of a series of case-specific tangible and intangible values that can be analysed and interpreted from different perspectives (Diesendorf, 2000[1]; Purvis et al., 2019[2]; Kwatraa et al., 2020[3]). These aspects are particularly evident in the case of extra virgin olive oil, where the nutritional value, the link with the territory, the environment, and social responsibility are added values and a marketing tool to attract and protect consumers. Nevertheless, with regard to the Italian olive-oil sector, the extreme fragmentation of the production structure, the different farming systems, the vast national olive germplasm, and the prominent economic, cultural (from gastronomy to medicine, from art to mythology and history), social and environmental value of olive, make it difficult to generically define a univocal model of sustainability. Accordingly, the drafting of a sustainability technical guide for the olive-oil supply chain was aimed at providing technical support for the Italian olive growers during the switch to environmental, socio-economic, and cultural sustainability practices. In order to accomplish this goal, we had to the”x-ray” the Italian olive-oil supply chain in terms of environmental, food quality/safety, social and economic sustainability. For this reason, we provided a participatory stage with the involvement of highly engaged and referenced stakeholders, and a validation phase with the involvement of 18 Italian olive companies during a pilot stage to test the effectiveness of the requirements and to build a constructive dialogue.

The technical guide has been developed on the basis of a paradigmatic, ideal company covering the entire production cycle, from farm gate to point-of-sale; consequently, it can be even administered to olive farms exclusively dealing with the agricultural phase, olive mills dealing with the stages following primary production and companies exclusively dedicated to bottling, packaging, and marketing, despite they cannot be considered the natural recipients of the guide, as they fall outside most of the provisions. For this reason, the non-applicability of a specific requirement is contemplated. The text has undergone some changes according to comments and suggestions of the companies involved, which were therefore not only passive subjects of this pilot study.

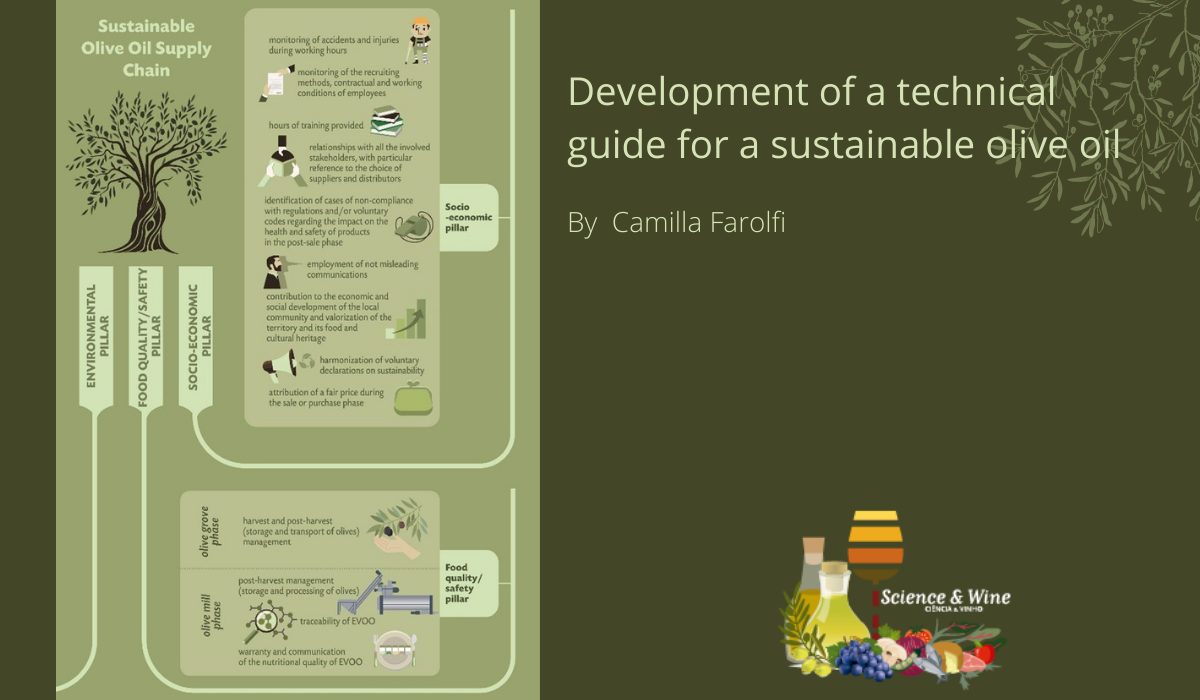

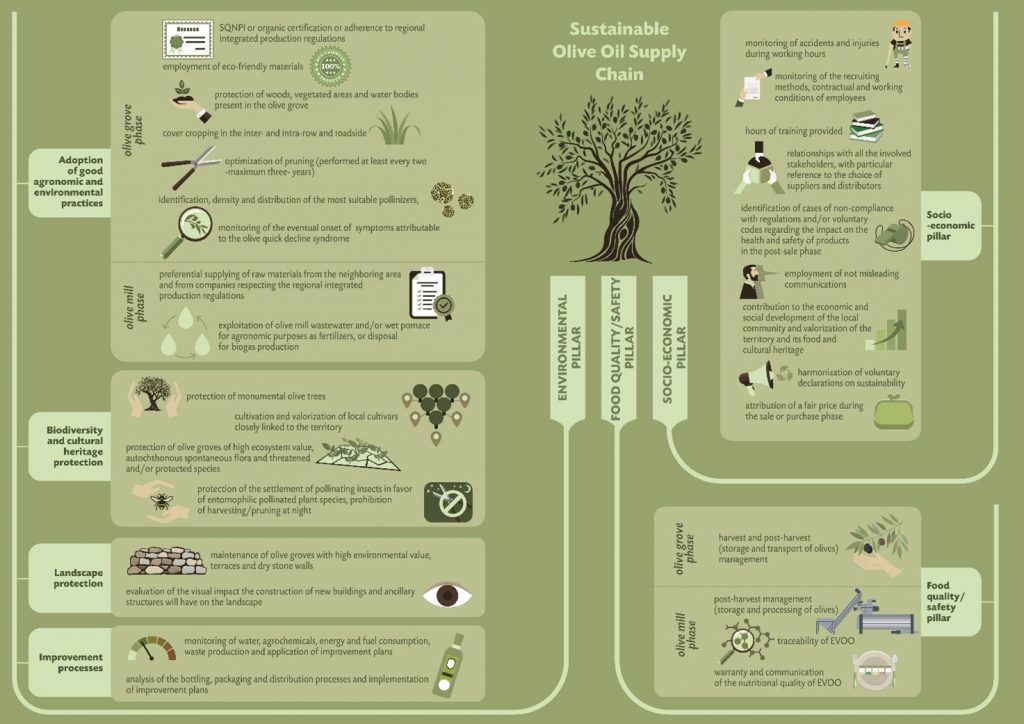

The specification is divided into 42 requirements catalogued according to the four pillars of sustainability (figure 2): Environmental (20), Food Quality/ Safety (6), Social (10), and Economic (6). However, a requirement may have several implications, thus falling into more than one pillar/category. Mandatory actions and indications of (voluntary) good practices are envisaged for each requirement; a requirement is met when all of its provided mandatory actions are met. The answer options are in the “yes”/”no”/ ”not applicable” form in reference to the mandatory actions only.

The goal of the technical guide was to obtain a highly inclusive text based on a limited number of requirements whose degree of compliance would have allowed for a general but accurate and comprehensive picture of an olive farm/company sustainability level. It was intended as operational support for the enhancement and promotion of a sustainable olive-oil supply chain by representing a point of reference for olive oil companies in the definition of a sustainability model and in the systematic implementation of improvement processes. At the same time, it can be a useful tool for policymakers to define the areas of economic intervention in supporting olive companies in a context of environmental and cultural heritage protection, premium quality production, fair income distribution, respect for workers’ rights, and profitability. Additionally, a sustainability technical guide can represent an aid for small farms in the transition to sustainable forms of agronomic and/or business management in order to access national or European financings that are traditionally more commonly requested by and granted to large farms. Eventually, it may serve as a touchstone for other olive-producing countries.

More details at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969722004247

Camilla Farolfi: graduated in Agricultural Science, now is a PhD student at the Department for Sustainable Food Process, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Via Emilia Parmense 84, 29122 Piacenza, Italy, about “Strategies for Sustainable Management in Olive Growing”. The research project aims to focus on critical management in olive cultivation in order to create a sustainable and profitable production system and to meet the demand for high-quality products and services. The project has several specific objectives: (i) the development of a single standard of sustainability for the olive oil supply chain; (ii) the effect of the variation in load on the oil yield, on the accumulation of metabolites, and on sustainability; and (iii) the evaluation of the response of olive trees to the availability of water.

[1] Diesendorf, M., 2000. Sustainability and sustainable development. In: Dunphy, D., Benveniste, J., Griffiths, A., Sutton, P. (Eds.), Sustainability: The Corporate Challenge of the 21st Centurychap. 2. Allen & Unwin, Sydney, pp. 19–37.

[2] Purvis, B., Mao, Y., Robinson, D., 2019. Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 14 (3), 681–695.

[3] Kwatraa, S., Kumar, A., Sharma, P., 2020. A critical review of studies related to construction and computation of sustainable development indices. Ecol. Indic. 112, 106061.