The Canadian wine industry is relatively small and young, but nonetheless growing and innovative. From its inception, winemakers in Canada have had to use ingenuity to find the most suitable micro-conditions in an otherwise rather harsh environment. The industry has developed around a limited number of regions in Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec. These regions are generally categorized as cool climate, meaning that the growing season is short, and the risks of winter injuries are high. These conditions have, of course, shaped the nature of wine production in Canada, with specializations in the Vitis Labrusca varieties in Quebec for instance, which are known for their greater resistance to cold, and the production of niche, but highly praised ice wines across Canada. Overall, the industry comprises just over 500 wineries and is mostly composed of small enterprises and family-run businesses. While the industry in Canada is certainly growing and there is now a larger appetite from consumers for local products, it is facing two important challenges that I am going to discuss here: global competition and environmental change.

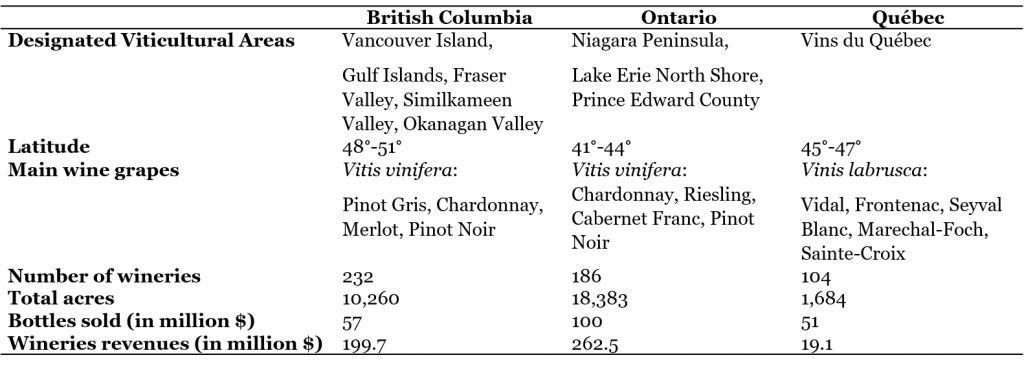

Sources: Canadian Vintners Association Economic Impact Study (2017); Winery & Grower Alliance of Ontario; Grape Growers of Ontario; VQA Ontario; BC VQA; Association des Vignerons du Québec. From Doloreux and Frigon (2019). Understanding innovation in Canadian wine regions: an exploratory study. British Food Journal 121(4).

The wine industry is globalized and dominated by traditional places that have built on centuries of know-how and experimentation to perfect their product and production methods. To be sure, there are also new players that are capturing important market shares on global markets. Most of these places, however, benefit from climates that are similar to the more traditional places, and the mobility of people and knowledge in our globalized world certainly allows people from different parts of the world to have access to fine production techniques. In addition, the example of California shows that some of these wine regions are also often supported by important industrial complexes and benefit from the availability of large amounts of capital to invest in scaling or in developing the infrastructure at large. There are indeed plenty of wealthy Californians that have been keen to invest in the wine industry and have their names on the bottle! This abundance in capital has allowed wineries to grow fast and be rapidly competitive on global markets. There is unfortunately little of these ingredients in Canada. Winemakers cannot build on centuries of knowledge about the land and the grapes, wineries are relatively small and lack the capital to invest in expansion ventures, and institutional support in research and development and commercialization has been uneven across geographical regions. It is therefore quite a challenge to compete on the market for Canadian wineries, and not only abroad, but also domestically, where Canadians tend to drink more imported than domestic wine.

The industry is thus facing giants when it comes to charming the heart of consumers. A study we conducted with my colleague David Doloreux, however, shows that Canadian wineries are not passive in front of this challenge. We found that most wineries were actively working on either developing and refining their product or designing new commercialization strategies. We also found that the overall patterns of innovation in the industry had a strong regional character. Quebec wineries, which are, on average, younger and smaller in comparison to their peers in other provinces, are more active in the further development of their own production methods, whereas wineries in Ontario tend to develop marketing innovations to a greater extent. The success of Canadian wineries will indeed depend on their ability to develop new products and processes that are competitive against the larger players, but the size and resources difference also call for support coming from policymakers.

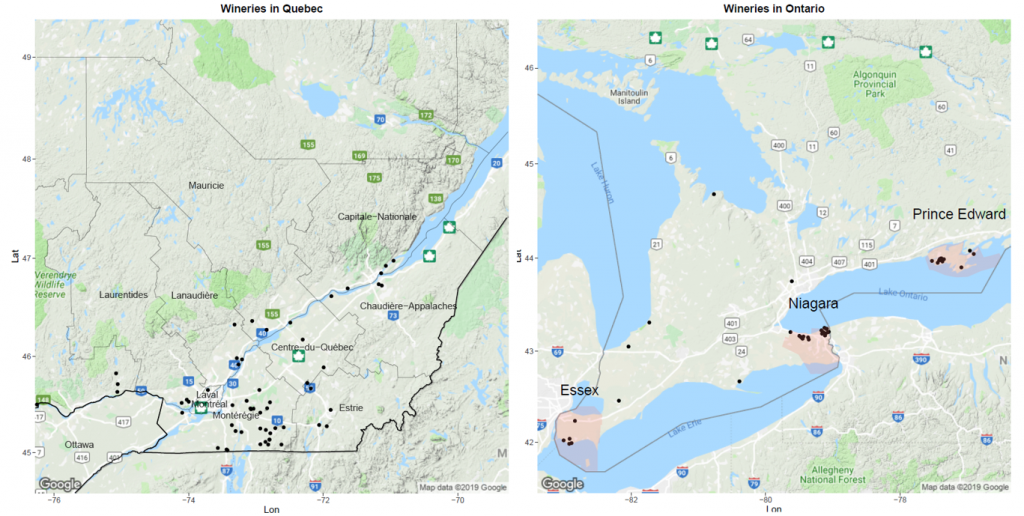

*The left-hand side map shows the location of wineries in Quebec, while the right-hand side map shows the location of wineries in Ontario with the designated viticultural areas colored in red. These maps clearly show that wineries in Canada concentrate around a few micro-regions.

The Canadian industry is also facing another type of giant: climate change. Of course, winemakers have already faced various challenges in terms of dealing with climatic conditions, but the broader patterns that we observe in terms of temperatures, frost days, extreme climatic events, might well push them to adapt even more. As an example, extreme weather events and a decreasing protective snow cover in the winter are likely to cause some damage to the vines, and thus represent additional costs for the winemakers. These changing conditions may certainly pose challenges but may also represent opportunities for the sector. On the one hand, some Canadian wineries perceive warming temperatures as an opportunity to venture into the production of new grape varietals (e.g. Vitis Vinifera) and thus appeal to a wider range of consumers. Increasing pressures coming from consumers and public authorities also push wineries to adopt greener practices and broaden their offer of organic products, which is believed to become an increasingly important market in the years to come. Some management scholars argue that adopting more eco-friendly practices in production processes may in fact result in a reduction in costs (reduction in waste) in the medium and longer-run, but that claim remains debated to this day. On the other hand, in some other circumstances, the additional costs coming from tighter environmental regulations could become a burden for the wineries and hurt their profitability, especially the smaller ones with fewer resources.

In a recent study with my colleagues David Doloreux and Richard Shearmur, we explored how wineries respond to these contextual changes and develop or adopt ecological innovations. We found again that the majority of wineries in Canada were quite active in that respect, for example by reducing their use of materials in production processes, by replacing materials with less greenhouse gas intensive alternatives, and by implementing recycling processes in the winery. Many of these technologies and processes are quite new to the firm, and we found in that respect that gathering knowledge from external sources was key to successfully transition towards more sustainable practices. These results highlight the importance of sharing knowledge between winemakers, and perhaps the necessity of supporting local organizations responsible for disseminating knowledge and technologies.

These are the challenges many wineries across the world face. How these respond to these challenges is key, as it is not only important from a local economic and employment standpoint, but also for our own opportunities to taste and experience wines coming from many different regions.

Read more at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124115

Anthony Frigon is a Ph.D. candidate in geography at the University of California, Los Angeles. His work focuses on the relationship between organizations, innovation, and geographical locations. He is currently conducting research on knowledge sourcing strategies in multi-locational firms in the US, as well as research on innovation in small and medium enterprises in Canada.