By Donald Drakeman and Ya-Yen Sun

With millions of tourists visiting wineries each year, cellar door operations contribute to the economic health of wine regions around the world. They are also crucial for the financial sustainability of many wine producers. But, so far, little attention has been paid to their role in environmental sustainability. To address this issue, we have created a method for measuring wine tourism’s carbon footprint. We applied it to Australia and learned that cellar door sales may be the most carbon intensive component of all stages of wine production and consumption by a very large margin.

This method can now be applied to other wine regions to determine how much of a carbon footprint is left behind by their wine tourists, and we encourage wine researchers to do so.

Measuring Greenhouse Gas Emissions

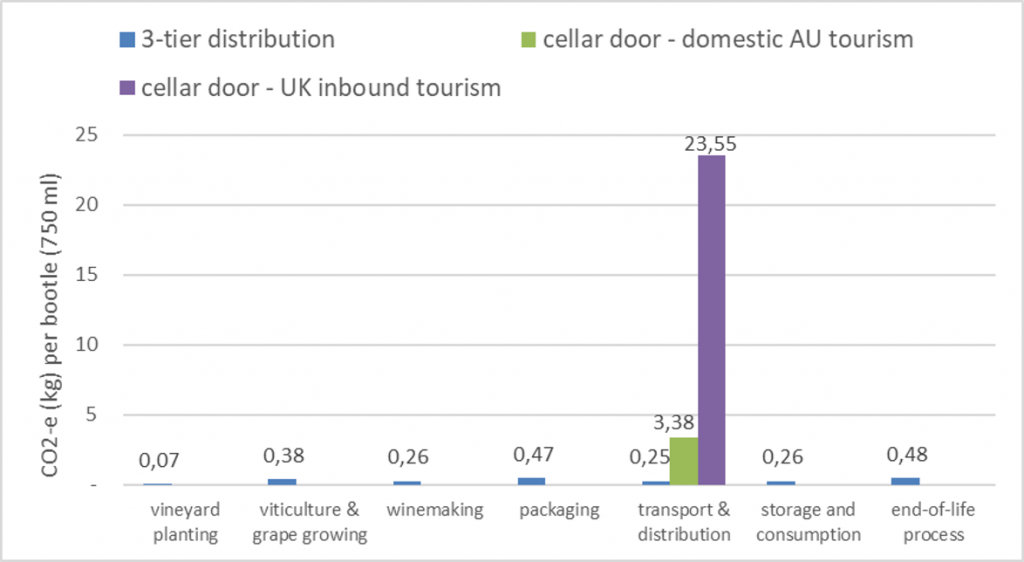

A comprehensive “cradle to grave” life-cycle analysis of wine’s carbon footprint involves numerous stages, including vineyard planning, viticulture and grape growing, winemaking, packaging, transportation and distribution, storage, consumption, and finally the end of life process. Wine tourism and cellar door operations act essentially an alternate transportation and distribution stage. Instead of the wines being shipped to distributors or retail stores for sale to consumers, tourism transports the consumers directly to the winery.

A life-cycle perspective of wine tourism’s carbon footprint consists of three steps.

Step 1: Calculating wine tourism emissions. Our approach takes two steps to calculate the wine tourism emissions for both domestic and international wine tourism. Emissions within Australia are calculated based on the amount of visitor expenditure on a series of trip components. It assumes that spending more money on a product or service leads to more emissions from that sector. Calculating total emissions involves multiplying visitor spending on various kinds of activities, such as air transport, accommodation and recreation, by the emissions associated with that sector. International aviation emissions associated with international inbound visits are provided by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) based on the distances between the original country and Australia’s major airports. Handling international aviation emissions separately is especially critical in the context of Australia because air transport is the most carbon intensive component of the journey, especially with respect to long-haul intercontinental flights.

Step 2: Allocating emissions to winery visits. The main question is whether wine tourism is the trip’s primary purpose. If so, emissions from the whole trip are allocated to winery visits. This is only about 0.1% of the international wine tourists traveling to Australia, but probably a much larger percentage of people reading this post. For merely “interested” or “accidental” wine tourists, the emissions for a half-day of the trip are included.

Step 3. Converting to emissions per bottle to allow benchmarking. We converted the per visitor calculations to a per bottle basis based on data collected about the average number of bottles purchased by wine tourists.

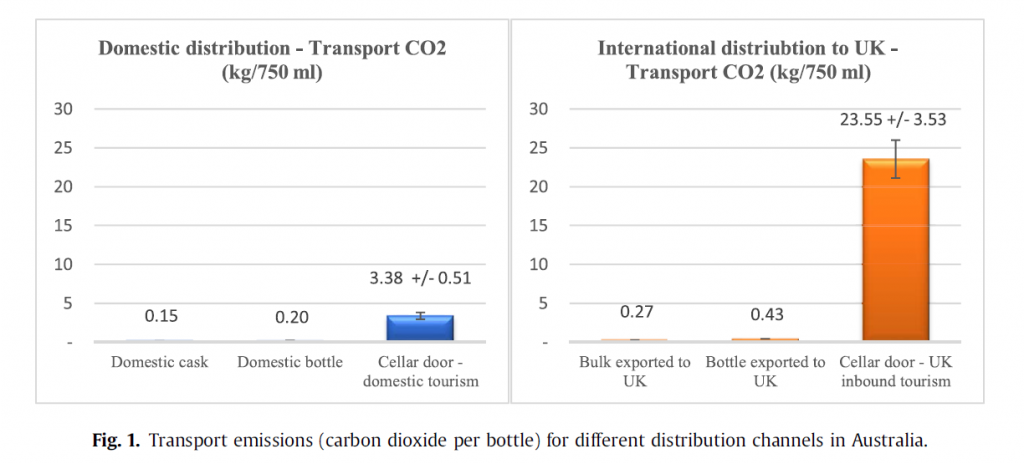

Results for Australian Wine Tourism. Figure 1 shows the emissions for a variety of possible distribution channels. Transporting wines to domestic wholesalers or retailers in casks produces the least amount of carbon dioxide. Domestic wine tourism facilitates direct-to-consumer sales at the cellar door but the emissions per bottle are about 15~19 times larger than sales at wine retailers. For international tourism, we compared the emissions associated with selling one bottle of wine to a UK wine tourist at the cellar door to exporting the same bottle for sale to a UK resident. The cellar door sales to UK visitors result in an 85-fold increase in emissions over exporting the wine to the UK. Across all distribution channels, selling one bottle wine to a UK visitor to Australia would produce emissions more than 150 fold greater than selling the wine in a two or four liter cask in a domestic retail store.

The second benchmarking analysis compared wine tourism with other stages in the overall life-cycle analysis, such as viticultural activities, winemaking, packaging, and end of life processes. Cellar door operations are the most carbon intensive component, at least seven times higher than packaging and end-of-life processes, which traditionally are responsible for the highest carbon intensity.

Summary. Cellar door wine sales to tourists are the most carbon intensive element of the wine life-cycle process, with carbon generation levels several times higher than the next highest component. On a per bottle basis, the largest carbon footprint in a “cradle to grave” life-cycle analysis is attributable to sales to international tourists, which can result in a more than 100 fold increase over domestic retail distributions. Even sales to domestic tourists lead to much higher carbon levels, at least 10 fold larger than domestic or international retail sales through other channels.

Although cellar door sales generate greenhouse gases that may negatively affect the wine industry’s environmental sustainability, wine tourism also offers many benefits. A regular inflow of visitors can be critical to the survival of many small and medium sized wineries. Moreover, wine tourism contributes to the cultural preservation and social stability of rural communities, and makes significant contributions to the economic and social sustainability of many wine producing regions. To understand both the costs and the benefits of wine tourism, it is time to add a consideration of its carbon footprint to the industry’s comprehensive efforts towards achieving both financial and environmental sustainability.

This post is based on: Sun, Ya-Yen and Drakeman, Donald (2020) Measuring the carbon footprint of wine tourism and cellar door sales. Journal of Cleaner Production, 266 121937.doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121937.

Donald Drakeman, JD, PhD, DipWSET, is a Fellow in Operations and Technology Management, Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, and Distinguished Research Professor in the Program on Constitutional Studies, University of Notre Dame (USA). d.drakeman@jbs.cam.ac.uk.

Ya-Yen Sun, PhD, is Senior Lecturer in the School of Business at the University of Queensland, Australia. Her research focuses on the macro-level evaluation of tourism economic impacts and tourism environmental impacts to the country. y.sun@business.uq.edu.au.