By Elói Jorge

There is a growing trend in the demand for organic products that should not be ignored. However, the figures reveal that consumers acceptance of organic wines is far behind that of conventional ones. The literature meant that consumer attitudes guide their behaviour. However, there is evidence that positive attitudes presented by consumers towards organic products are often not reflected in their willingness to pay for organic wine. This conflict falls into the so-called attitude-behavior gap. In this study it is argued that the higher ambiguity associated with organic wines, in comparison with conventional ones, is a possible explanation for this gap.

Ambiguity is the absence of the information necessary to understand a particular situation (McLain, 2009), and an individual is facing an ambiguous situation when he/she is incapable of adequately structuring or categorizing the situation due to contradictory or insufficient cues (Budner, 1962). In an organic wine context, ambiguity is mainly related to the “amount,” “unanimity” and “reliability” of the available information referring this concept (Ellsberg, 1961). In this regard, this study argues that the ambiguity associated with organic wine could derive not just from the existence of multiple production process regulations (e.g. international, national, and regional), several similar concepts (e.g. sustainable, organic, organic, “bio”, carbon footprint, or biodynamics), and a wide variety of certification labels (e.g., public/official and private). Yet, it’s a fact that during the decision-making processes, individuals will interpret and react to information differently. This behavior, to a large extent, is due to their tolerance to ambiguity, with those with low levels of tolerance of ambiguity needing a higher amount and more precise information than those with higher levels.

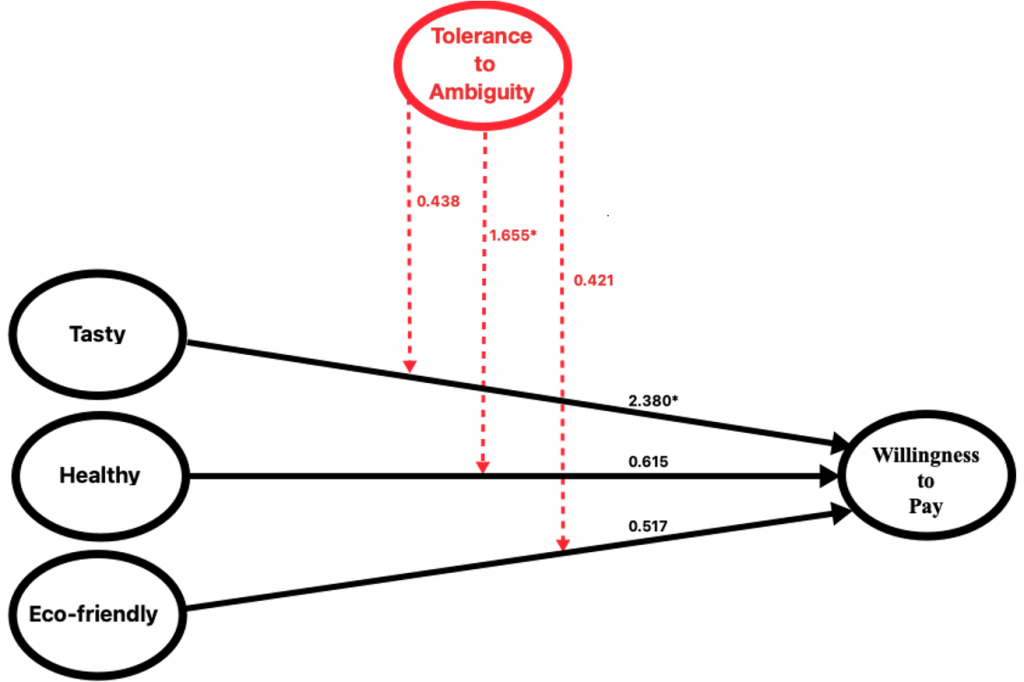

The study focused on analyzing the impact of the three most recognized attitudes towards organic products. In particular, the one related to the sensory aspects of food (tasty), the consumers’ perceptions about health gains due to consumption of organic products (healthy), and the one associated to the pro-environmental concerns of the potential buyers (eco-friendly), on the willingness to pay for organic wines (Figure 1). In the context of attitude-behaviour relationship, this work incorporates the influences of the theoretically meaningful, yet underresearched, moderating effect of the tolerance to ambiguity personality trait, in an attempt to explain the attitude-behavior gap.

Figure 1. In black it is represented direct relationships between consumers’ attitudes and their willingness to pay behaviour for organic wine. The moderator effect is represented in red. The positive and significant relationships are marked with an asterisk (*).

For this research, and following prior studies, a wine lab experiment was conducted along with two questionnaires. Participants in the lab experiment were requested to place different bids for each one of the wines at their disposal (Figure 2). Willingness to pay was calculated by comparing the amount of money bid for an organic wine with the one that was bid for a conventional wine with the same Protected Designation of Origin certification, geographic indication, varietal grape and type (young red). Participants were asked to answer two questionnaires, one before and the other during the experiment. Here, beyond demographic data, it was measured participants individual attitudes toward organic food, and their tolerance of ambiguity.

This study found that consumers positive attitudes towards organic products do not always reflect their behaviour in purchasing these products (Figure 1). The results show that when consumers believe that organic wines have a better taste than the conventional ones, their willingness to pay for such products will increase significantly. It is also suggested that the positive influence of consumers healthy attitude (the belief that organic food is healthier) on their willingness to pay for organic wine is weaker in individuals less tolerant of ambiguity. Furthermore, no evidence was found signaling that consumer tolerance of ambiguity had a significant effect on the link between tasty or eco-friendly attitudes and willingness to pay. This finding is in line with a stream of literature that proposes that even when consumers perceive the positive environmental effects of organic wine production, it does not seem to be sufficient for them to choose an eco-friendly wine.

One of the significant issues facing the organic food industry is to increase consumer acceptance of its products. The conclusions are useful, as that brings new ideas for the marketing of organic wine. These findings highlight that the influence of attitudes toward organic food on purchasing behavior is not the same among all consumers. Those with higher levels of tolerance of ambiguity result in a stronger positive relationship between those attitudes and the willingness to pay for organic wine. Thus, the design of strategies that take into account the effects of consumer tolerance to ambiguity availability to pay for organic products could be especially relevant to the organic wine industry.

Those interested in the study can find it at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095965262030648X?via%3Dihub

Elói Jorge is a member of the research group RGEAF (Research Group in Economic Analysis Accounting and Finance) – ECOBAS, Faculty of Economic & Business Sciences, University of Vigo, Campus Lagoas-Marcosende, Vigo, Spain. This study, carried out together with Ernesto López-Valeiras and Maria Beatriz González-Sánchez, is part of a larger research project on consumers’ attitudes and behaviors towards sustainable products, and was partially funded by Diputación de Ourense (INOU 17-10) and RGEAF-ECOBAS (Xunta de Galicia).

References:

- Budner, S., 1962. Intolerance of ambiguity as a personality variable. J. Pers., 30 (1), 29-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1962.tb02303.x.

- Ellsberg, D., 1961. Risk, ambiguity, and the savage axioms. Q. J. Econ.,75 (4), 643-669. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884324. McLain, D. L., 2009.

- Evidence of the properties of an ambiguity tolerance measure: The multiple stimulus types ambiguity tolerance Scale–II (MSTAT–II). Psychol. Rep.,105(3), 975-988. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.105.3.975-988.