By Matthew McSweeney

Generally, panellists involved in sensory panels can be selected from two categories based on the purpose of the study: either consumer panellists or trained panellists. Trained panellists are selected based on their sensory acuity for basic characteristics (tastes, odours and textures) and their ability to discriminate among products. Trained panellists receive training on the background of the food products being tested and method of evaluation, and can identify small differences in the food products. Conversely, consumers or untrained panellists are usually used to complete hedonic tests where they are asked to indicate their preferences. It is unlikely that the untrained panellists can differentiate the small differences between the products.

Another group of panellists that can be considered for sensory panels is experienced panellists. Experienced panellists are participants who are highly experienced with the food product being tested, the method being used or who have received extensive training before the testing. One type of experienced panellists are those who do not have extensive knowledge of the food product being tested, but rather have experience with the sensory method being used. The other type of experienced panellists have a thorough knowledge of the products being tested. In studies involving wine, these experienced panellists are usually sommeliers, winemakers and others involved in the wine and grape industry. In this study, sommeliers, winemakers and others involved in the wine industry will be referred to as experts and panellists that have experience with the sensory method will be called experienced panellists. This study aimed to determine if different groups of panellists may evaluate wines differently. As such, each group of panellists used the projective mapping (PM) and ultra-flash profiling to evaluate single varietal white wines produced in Nova Scotia (NS), Canada.

These methodologies can be adapted to panellists with different degrees of training (Ares & Varela, 2017). Projective mapping asks panellists to represent similarities and differences between products and leads to a graphical representation of a product to understand relationships between products. Projective mapping is considered to be a holistic approach that allows participants to express similarities and differences, as well as group samples by positioning them on a two-dimensional plane using either a piece of paper or a computer screen (Santos et al., 2013). Projective mapping is usually paired with ultra-flash profiling (UFP). In the UFP method, participants are asked to use their vocabulary to list adjectives next to each sample after they complete their projections.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the results of a projective mapping and ultra-flash profile task on single varietal white wines completed by experienced panellists, and compare those results to those produced by trained panellists, naïve consumers, and individuals employed in the wine industry (experts).

The experienced panellists were composed of 17 individuals who had participated in PM and UFP trials previously (7 males and 10 females; mean age of 33.8 +/- 6.4). The trained panellists consisted of 11 individuals who had previously participated in two trained panels describing white wines produced in NS (4 males and 7 females; mean age of 26.1 +/- 5.4). Eighty-two consumers (38 males and 44 females; mean age 33.9 +/-12.1) participated in the study and twelve experts (sommeliers, winemakers, wine professionals, grape growers, mean age 38.2 +/-5.6) from the NS wine industry. Each group of panellists were asked to evaluate seven single varietal wines, and one sample was presented twice (W5). The participants were instructed on how to complete a PM and UFP task, and the results were evaluated using Multiple Factor Analysis. RV coefficients were used to determine the degree of similarity between results from the different panellists.

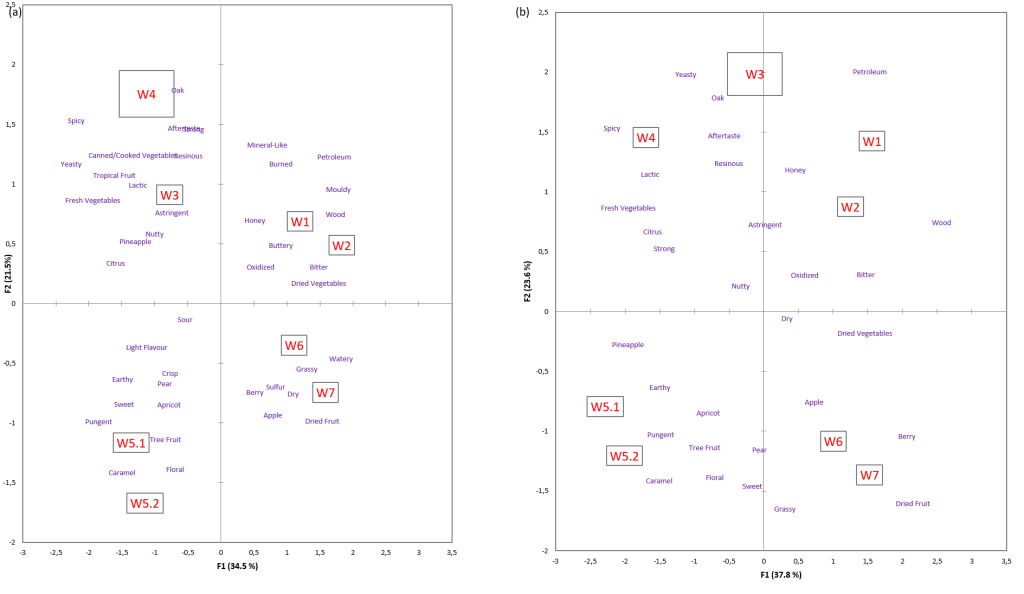

The results of the sensory task completed by the different groups of panellists indicated that experience with a sensory method affected the results. The experienced panellists’ results were similar to that of the trained panellists (RV=0.768); however, they were not similar to the consumers (RV=0.431) or experts (RV=0.260). The results of the PM and UFP task completed by the trained panellists and experienced panellists can be seen in Figure 1. Additionally, in Figure 1, the experienced panellists (Figure 1a) and trained panellists (Figure 1b) placed the blinded duplicate samples (W5.1 and W5.2) very close together. The experts also placed the duplicated samples close together, but the consumers did not (biplots not shown). These results indicate that the experienced panellists’ familiarization with the PM and UFP task improved their performance. Comparing the results of the trained panellists to that of the experts and consumers using the RV coefficients (RV= 0.156 and 0.275, respectively), found the panellists evaluated the wines differently. Differences between trained panellists and consumers have been found in many studies on wines, as has the differences between trained panellists and consumers. Experts had also been found in past studies to evaluate wine differently than consumers, and this was found in this study as well (RV=0.308).

Overall, the experienced panellists evaluated the wines similarly to the trained panellists, and if wineries have a pool of experienced panellists (familiar with the method), they may be able to save money when evaluating the quality of wines before they are released to the public. The experts (those involved in the wine industry) evaluated the wine samples differently than the trained panellists and the consumers. Wine producers should be mindful that experts’ evaluations of wine may not always correlate to that of consumers. In conclusion, participants’ level of experience affects the results of a sensory task and must be taken into account when conducting sensory trials, in this case, specifically when evaluating white wines.

Those interested in the study can find it at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0950329319308821

Matt McSweeney is the director of the Centre for the Sensory Research of Food (CSRF; Acadia University, Wolfville, Canada). This study is part of a larger project investigating the sensory attributes of wines produced in Nova Scotia, Canada. The project is being conducted by the Centre for the Sensory Research of Food and is funded by the Nova Scotia Department of Agriculture. The CSRF is committed to helping undergraduate students obtain training in food product development, food chemical analysis, and sensory analysis. As such, this study was conducted by Lydia Hayward and Alanah Barton, two undergraduate research assistants, within the CSRF.

References

Ares, G., & Varela, P. (2017). Trained vs. consumer panels for analytical testing: Fueling a long lasting debate in the field. Food Quality and Preference, 61, 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.10.006

Santos, B. A., Pollonio, M. A. R., Cruz, A. G., Messias, V. C., Monteiro, R. A., Oliveira, T. L. C., Faria, J. A. F., Freitas, M. Q., & Bolini, H. M. A. (2013). Ultra-flash profile and projective mapping for describing sensory attributes of prebiotic mortadellas. Food Research International, 54(2), 1705–1711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.09.022

[…] Science & Wine: Do different panellists (experienced, trained, consumers and experts) evaluate w… […]